Matthew Braunginn

This is part two of a two-part series on how we can prevent the coming collapse of the global food system.

Our relationship with food and water and one another are a large part of why the

United States and ”Western civilization” are breaking at the seams. A (not

exhaustive) list includes how our farming techniques destroy the soil and sea life,

that food recalls are common, and the way we eat (not only because of what is

available) is unhealthy. Creating a revolution of values is a way through this;

regenerative practices are actualizing this revolution.

Richard Elm-Hill, lead program officer from First Nations Development Institute,

spoke with Daily Kos about how communal food is, using cooperative farming as an example. In western cultures you’ll often see a farmer's co-op, and the plot will be equally divided up between farmers. But for Elm-Hill, if “we do everything

communally, we’re all going to grow together as families, we’re all going to share

the space.”

We’re already seeing some of these things break through, such as the growth

of urban farming. But that is just a small step to fix what is broken. A different way

to think about food access and our relationship with food would be to ask, what if

we designed urban environments around community, people, water, and food? To

Elm-Hill, “you can go into any Native community, and they will paint you a picture of a beautiful food system … societies that are built on top of the foods themselves

when you have that deep relationship with the foods, that might be what's missing

in modern agriculture.”

Many Americans are removed from their food: where it comes from, what’s in it,

how we access it, prepare, and eat it. It’s a shallow and transaction-based

relationship. Changing our relationship with food is healthier too: According to

Farming our way to starvation: Land stewardship and Indigenous agriculture the American Heart Association, people who create intentional spaces to share and

eat food together live healthier lives.

Regenerative practices don’t just link to local interconnected ecosystems but global

ones. The Amazon rainforest is being cut down to become farms, mostly to feed

animals being farmed in a destructive manner, just as fisheries are using wild-

captured fish as part of the feed for fish farms. Animals actually play a role in

regenerative farming through controlled rotational grazing, helping capture CO2,

fertilizer from animal waste, and pest management. And when we encourage the

biodiversity of animals as opposed to fencing them in, it helps restore the lands and seas around us.

In partnership with Indigenous nations

There are dangers as these practices scale. Major food giants General Mills and

Kellogg Company are partnering with organizations talking about regenerative

practices, and while the companies adopt the technical aspects of regenerative

farming, they leave behind the social and philosophical, replicating colonialism and the current flawed systems. While using techniques to “restore” the land,

differentiating from sustainable agriculture, this branding is not restorative. It fails

to engage Indigenous populations and incorporate Native land stewardship, it

doesn’t change America's relationship to food, and it’s more focused on the

restoration of farming plots than the wider ecosystem. Put it this way: It primarily

focuses on each farm, not what is down or even upriver and how it all

interconnects.

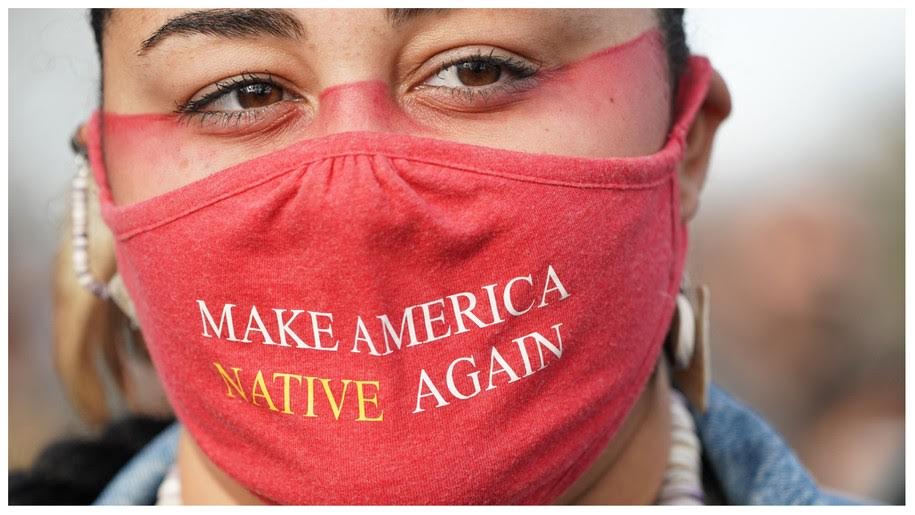

Regenerative practices should only be adopted with engagement and partnership

with Indigenous people and nations. There is a link between adopting Indigenous

regenerative practices and landback calls. Landback is part of a more significant

decolonization movement that calls for what the name suggests: returning stolen

land. The nuance of it is important too; it’s about the sovereignty of Native Nations, having stewardship over their own lands and national parks, having power over practices that harm their (and our lands), and embracing a cooperative relationship with each other and our shared land.

Regenerative practices are further explained in this Teen Vogue piece by Ruth

Hopkins, where Nick Tilsen, president and CEO of NDN Collective, expounds: “We're going to get back to prioritizing the relationship between the land and the people, rather than thinking about the land as just something that we should extract from for the purposes of money and power. We're reclaiming our inherent right to assume control, protection, and stewardship of these lands.”

Stewardship is crucial. Marco Hatch, an associate professor of Environmental

Science at Western Washington University and a member of the Samish Indian

Nation, explains to Daily Kos, “These are our areas we’ve stewarded for millennia,

and this is reclaiming our place on the tideline of the beach. In often large, visible

ways this is an acknowledgment that Indigenous people have maintained and

managed intertidal ecosystem beaches [ where the ocean meets the land, with high

or low tides ] for thousands of years, and it’s a restoration of that practice.”

Where these practices are being developed, a lot can be learned. The lesson of

nature’s resilience should not be lost. In drought-affected parts of Mexico,

regenerative practices have created resilience and healed the soil from its past poor

state. Dimitri Selibas of Mongabay (a nonprofit conservation and environmental

science news platform), writes about how regenerative practices have restored

fields to the point where enough water is in the subsoil to last for 40 days of

drought, where before, crops would be destroyed before they could grow.

Regeneration is possible in the sea too; coral reefs can heal as well when human

interference is prevented. As much as our practices have been destructive, if we

change how we engage with our planet, it can heal and actively help us.

How we need to change

Regenerative is about breaking down walls and decentering humans, instead seeing us as one piece—with immense effect—of a complex ecosystem. And it’s about how our governments need to be willing to engage with Native governments.

Elm-Hill emphasizes the sovereignty of Native Nations, saying a “key part of having sovereignty is that you’re in a nation-to-nation relationship.” This relationship applies to regenerative practices being adopted, as Elm-Hill continues, “because a lot of coastal tribes or waterway located tubes have a good understanding of what that ecosystem looks like in a healthy state, there should be a lot of asking when we’re looking at specific parts of say, the coast. You know: What’s happening here, what are the changes, what do you see, what do you want to happen?”

Governments must consult early with tribes when making decisions on natural

resources, and tribal governments should be treated as equal partners in the

stewardship of this land. What could this look like? California has just passed

land stewardship of 200 miles of coastland back to five different tribes in the state,

and in early 2022, the California state government did the same with their Redwood Forests. U.S. National Parks are increasingly seeing co-stewardship between Indigenous peoples and the National Parks Service, with currently over 80 such agreements in place . This progress is just the start of what the governments of the United States need to do.

Individually, we can take collective steps, especially for those of us who are not

Indigenous. Elm-Hill says the first step is for us to learn Native and global

Indigenous history and culture. I “think there’s a lot to be said in learning the

history, whatever tribe where you live, that was, is or was their land, go read about

them and go read everything you can. … Once you have that knowledge base,

you’re going to run into what was done on the land, what was the food system,

you’re going to run into all the injustices, some badass leaders and characters,

you’re going to cry a little bit, you’re going to know how you feel about your place in that space. If you don’t come in having done that history work, it’s kind of at your own loss.”

Food can be a shared resource

One of the biggest lessons from regenerative agriculture is seeing the genuinely

diverse ways to be human. Food doesn’t have to be a scarce and controlled

resource but instead a communal one. Instead of thinking about resources as

something to extract, control, and hold power over, they are something to cultivate

and share.

It is incumbent upon us to recognize the failures of these Western systems and

practices and to see our failing ecosystems, social connections, and social health as

rooted in these dominant systems and practices. The failures of these systems have

always been pointed at those the systems oppress the most: global Indigenous

peoples, immigrants, Black people, and other marginalized groups.

So we must learn, read, and study those who understand this. Study Native history, and ask how we can put food and water at the center of our being, our

communities, and our connective nature. Then use food and water to build your

community, embracing this connectedness. Hatch ended the conversation by

asking readers to do what he asks his students to do: “imagine yourself as a drop of

water, and to think, where are you going to go if you fall here, in the middle of

Western Washington University’s campus (or wherever you are). What’s your path

to the sea?”

Thought experiments like that can help us understand the world in a different

way—by letting go of “me and mine,” of our possessive nature, and western

practices of trying to isolate everything. We can adopt the words of Elm-Hill: “Part of what we're doing here … is to live in this shared space in a peaceful way.”

Ready to learn more? The First Nations Development Institute has resources you

can find on their online knowledge center. A here are few books to get you started:

-

Unworthy Republic: The Dispossession of Native Americans and the Road toIndian Territory by historian Claudio Saunt

-

Killing the White Man's Indian: Reinventing Native Americans at the End ofthe Twentieth Century by Fergus M. Bordewich

-

An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by Rozanne Dunbar-Ortiz

-

Red Earth, White Lies: Native Americans and the Myth of Scientific Fact byVine Deloria Jr.

This story was produced through the Daily Kos Emerging Fellows (DKEF) Program. Read more about DKEF (and meet the author, and other Emerging Fellows) here.