LAS VEGAS – The head of a federal agency that spends $75 billion annually on federal contracts wants to work with tribes on clean energy projects that can deliver a “triple win” for tribal citizens and the planet.

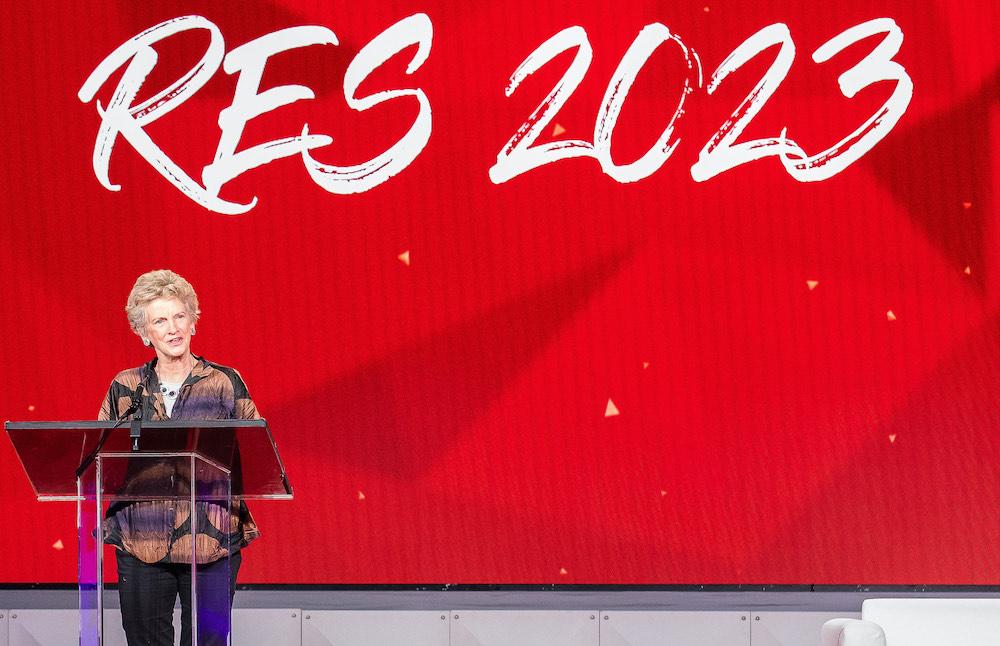

Robin Carnahan, administrator of the U.S. General Services Administration, delivered that message in formal remarks last Monday morning at the 2023 Reservation Economic Summit (RES) in Las Vegas. She also hosted a formal Tribal consultation Monday afternoon for about 100 tribal leaders who attended the annual economic development conference for Native Americans.

During both sessions, Carnahan talked about emerging opportunities for Native-owned businesses to work with the federal government and reaffirmed the Biden administration’s pledge to build strong Nation-to-Nation partnerships with tribes.

She highlighted opportunities for Native-owned businesses including small business contracting with the federal government, partnering with GSA to procure electric vehicles, and a pilot program to support federal buying of carbon pollution-free electricity from Tribal organizations.

GSA is interested in working with tribal nations on projects that will advance clean energy development and deliver a “triple win” for Indian Country— good-paying jobs for tribal citizens, new energy projects for Native businesses, and overall good for the planet and future generations, she said.

In her morning remarks, Carnahan said the federal government spent $20 billion with Native American businesses in fiscal 2022. More than half of that amount — about 57% —went to Alaska Native organizations with the remainder split among tribally owned enterprises (22%), individually owned Native firms (15%) and Native Hawaiian firms (6%).

The $20 billion spent with Native businesses represented just 3.3% of the federal government’s total spending last year, Carnahan said, noting that the GSA’s spending with Native-owned firms was about 7% of its total purchases last year, and 57% of those contracts were competitively bid.

Looking ahead, Carnahan talked about opportunities where — and how — the GSA can work more closely with Native-owned firms, including infrastructure projects.

Over the next few years, for example, the GSA will spend $3.5 billion on 26 projects at land-based ports of entry along the country’s northern and southern borders. Indian Country spans more than 260 miles of those borders, Carnahan said.

A recent port-of-entry project could provide “a model to build on” for future GSA projects that impact Indian Country, she said. Earlier this year, GSA was working with the U.S. Customs and Border Protection on a project on trust lands along the Canadian border. They hit pause on the planning process in order to hold nation-to-nation consultations with tribal Leaders and address concerns from the Grand Portage Lake Superior Chippewa tribe in northeastern Minnesota.

“That consultation was extremely valuable in helping the GSA team reframe its thinking about the project and in forging a cooperative relationship built with that Tribal Nation,” she said.

The Biden administration’s efforts to electrify the federal fleet and build a clean energy economy also offer other areas for collaboration between the GSA and Native American businesses, according to Carnahan.

As the largest buyer of vehicles for the federal government, GSA can play an outsized role in the purchase of electric vehicles (EV) — including light-duty vehicles, buses, and healthcare vehicles — used by tribes in Indian Country. Because it buys so many vehicles for the federal government, GSA has close relationships with auto manufacturers and is able to negotiate “good prices,” Carnahan said. “Buying through GSA means you all can share those benefits.”

GSA’s ability to buy at scale also includes procuring clean energy, including electricity that minimizes or eliminates carbon pollution. Along with the Department of Defense, the GSA is one of the primary buyers of energy for the federal government. That positions it to work closely with tribes on clean energy projects.

“We know this transition will take time and a lot of collaboration,” she said. “That’s why my team and I are already talking with state utility regulators, energy companies, and suppliers as well as other government agencies to help ensure all of us are aligned and moving forward together.

“We’re eager to have Indian Country at the table early in those conversations because we know you’ll be crucial partners to GSA and the federal government more broadly as we make this transition to a clean energy economy.”