Paige Willett, Citizen Potawatomi Nation Public Information Department

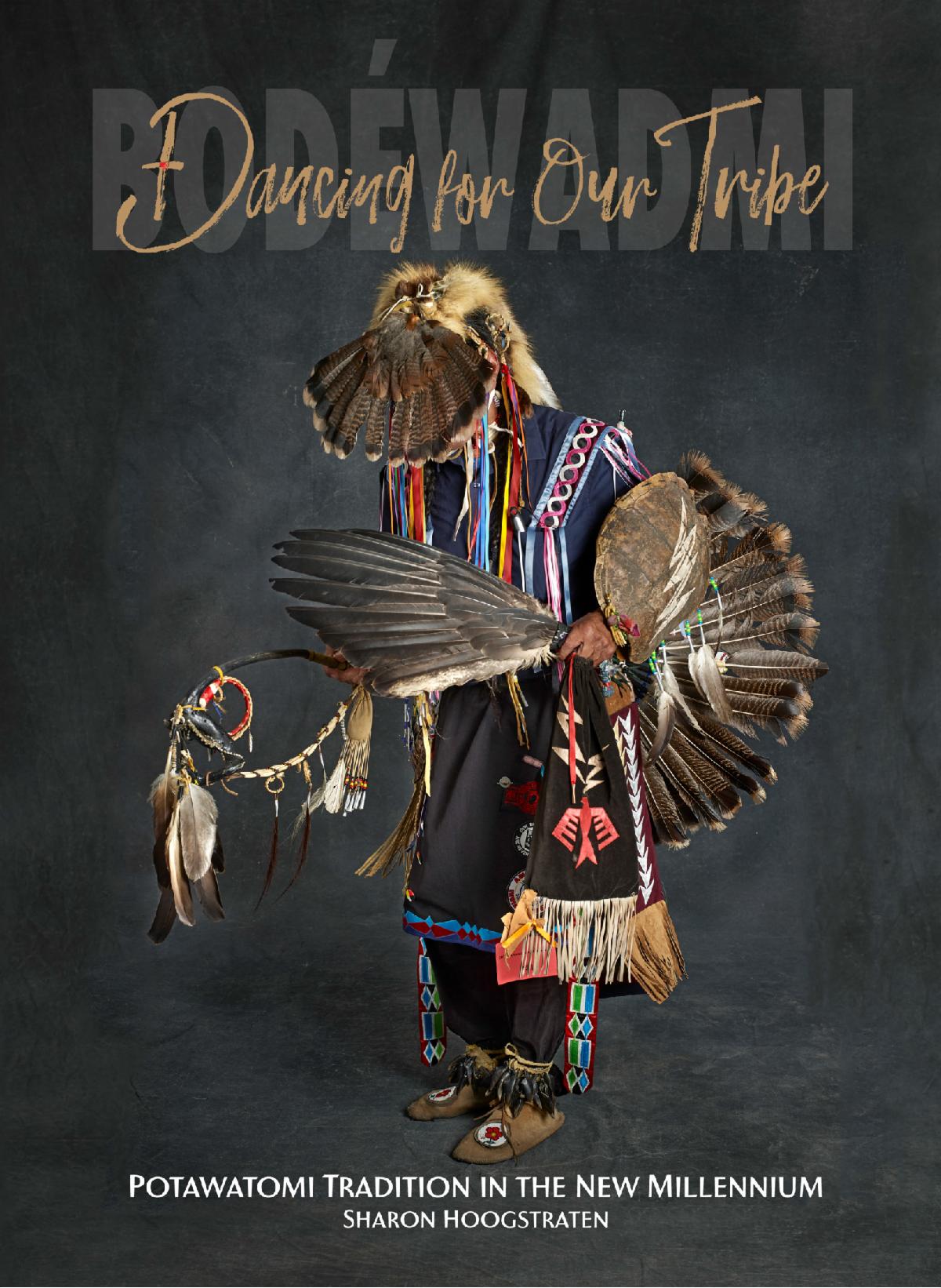

Since 2010, Chicago photographer and Citizen Potawatomi Nation tribal member Sharon Hoogstraten has been documenting members from the Potawatomi nations across North America for her book Dancing for Our Tribe: Potawatomi Tradition in the New Millennium.

Throughout the last 12 years, she has attended many events to capture the images that comprise the book she released in August 2022. More than that, she also collected family stories, Potawatomi history, poems, descriptions and artwork — all featured.

“I felt it was important to make the best, finest book I could because this is an heirloom. …This is supposed to go forward to the next seven generations. And in order to be saved and cherished in that way, it has to be a beautiful book,” Hoogstraten said.

Having honed her skills for nearly 40 years studying and working on various projects, she applied them to Dancing for Our Tribe. She designed every aspect of the book and filled every inch with her experiences and subjects’ knowledge and thoughts.

Regalia

During the photoshoots, Hoogstraten set up spaces for people to dance dressed in their regalia, capturing the beauty of the handmade creations in motion. For the most part, she said people overcame their self-consciousness and expressed gratitude for the opportunity.

“I thought that was amazing because we would use music, and we’d get caught up in the drum beat, and they would really give of themselves. And there is their personality in those images. They’re not catalog pictures. Their humanity is in there, not just their regalia. I always hope that people see that,” Hoogstraten said.

She enjoyed picturing people in their own cultural garments that transcend and show the influence of time and history.

“Regalia is not a reenactment. … This is a very based-in-tradition but current art. It is your story. Your regalia is always changing. It’s never finished. You are building your stories and your thoughts into your regalia. And then for non-Natives, it is a testimonial to the fact that we are still here, which so many people don’t understand,” Hoogstraten said.

While creating the book, she requested that her subjects handwrite statements about their attire, clan or Potawatomi family histories. Their handwriting became as important as their words.

“In our culture, the storyteller is the guardian of our history. … And that really resonated with me. I thought, ‘That’s what I’m trying to do here — be a guardian of our history.’ Once I started looking at it like that, then I could really start processing people’s stories of their regalia,” Hoogstraten said.

The book’s front flap reads, “Tribal members learning the art of regalia will find these portraits provide an inspiring reference.” Hoogstraten hopes it encourages Tribal members to make pieces of their own for the first time or pushes them to begin a new set for themselves or someone they know.

Past and present

Hoogstraten’s connection to Potawatomi culture and her heritage remained limited until she began the project despite living on Nishnabé homelands in present-day Chicago. A Ouilmette family descendant, she became inspired to learn about her ancestors and their past as she traveled throughout the continent, photographing other Tribal members. Now, her new book shows the breadth and depth of that gained knowledge.

“That’s been the thing with this project — every direction you turn, there’s a whole new tributary of Potawatomi history that is so interesting in itself,” Hoogstraten said. “But at some point, you just have to cut it off. This book is … like an encyclopedia. I mean, it’s 304 pages. It’s an inch and a quarter thick. And I couldn’t even put everybody in here.”

She wanted the focus to remain on regalia. However, the book also contains historical resources and engravings of artist George Winter’s sketches from the Potawatomi Trail of Death, when the U.S. government forcibly removed Tribal members from the Great Lakes to Kansas. The pages include contributions from Native artists and authors alive today depicting culture and history as well. The line drawings of feathers and birds are attributed to CPN artist Penny Coates.

“I tried to provide enough background so that people who want to pursue a deeper understanding of the history of the Potawatomis or even the Native American experience during colonization find books in the preface that I recommend they go to because I’m not an academic. I’m a photographer … although I have learned a lot in the last 10 years,” Hoogstraten said.

She made a name for herself throughout the Potawatomi nations during that time and enjoyed building relationships and meeting new family members.

“The reward … is from being a person who hadn’t ever been to a (Potawatomi) Gathering or a Family Reunion Festival until 2010,” Hoogstraten said. “I now feel so connected to all these people and all these Nations. You have to earn that, and it’s such a gift. It’s a treasure to me that I can go to these places, and people know me, and I know them. It’s huge.”

“My” to “Our”

At one point, Hoogstraten slightly changed the book’s title. While it may seem small, to her, the distinction carried significant weight.

“I had a working title, Dancing for My Tribe, because this was my personal project. And it wasn’t really until I started to put the book together that I thought, ‘We’re all dancing in this book.’ … The contributors, the assistants, even people who posed but aren’t in the book, they all contributed to the spirit of the book. And everybody was so generous with themselves and their time and their interest in the project that I felt I had to change the name to Dancing for Our Tribe. We’re all dancing in our own ways,” she said.

The transition from “my” to “our” came as Hoogstraten met more people from different Potawatomi nations and realized their stories about regalia and life needed to be included. She cherished every chance to learn from someone.

“Even if they say something that you already know or you assumed, there’s always going to be an edge on it that is different from the way you process it. So many times, I’ve thought I had things figured out, but I’ve learned to just shut up and listen. It always pays off. I already know what’s in my brain. I need to hear what’s in other people’s thoughts,” Hoogstraten said.

Throughout the years, she and her subjects worked in all climates and conditions, with shelter and electricity as necessities for a photo shoot. However, they were not always easy to obtain, and Hoogstraten was grateful for any help.

“I froze to death on Walpole Island (First Nation in Canada), shooting in the hockey rink. I was sweating to death at the Prairie Band (Potawatomi Nation in Kansas) because it was 105 degrees, and we were shooting in a machine shed with hornets and spiders. … And people look so good, and I wonder, ‘They’re in full regalia and dancing. I’m complaining about how hot I was. How did they do it?’ And nobody ever complained,” she said.

Creating an heirloom

Hoogstraten considered nearly every type of camera and format when deciding what kind of photography equipment to use. She filled the book with vibrant, full-color photographs with crisp lines that show off each piece of regalia and its wearer with the help of a high-resolution digital camera to ensure the preservation of the photos for decades and generations to come.

“You see modern photographers doing these beautiful portraits of Native Americans, and they’re black and white, and they’re very nicely done. I didn’t feel like I could do that because I’m showing exactly where we are in our time,” Hoogstraten said.

As the purpose grew from capturing portraits to telling Potawatomi stories, she started to feel a sense of obligation to her subjects and assistants, as well as the pressure of completing what she started. Hoogstraten used the additional time at home during the pandemic to put the finishing touches on the book and develop a production and distribution strategy. However, as supply chain issues worsened and costs for materials rose, it became a challenge.

“I owe all the people who participated in this, who put their time and trust in me,” Hoogstraten said. “That’s what scared me so much when I just felt like I didn’t know what to do anymore with the book being too expensive, no paper being available. It wasn’t so much a question of my legacy as I owed all these people a result. And it was very scary for me not to know what to do about that.”

After some uncertainty, the University of Oklahoma Press agreed to market and distribute the book. When prices escalated wildly, they recommended a printer, and Dancing for Our Tribe became available in August 2022.

“I look at all the work I went to and I know so many Tribal members go to find their ancestors. They’re digging through photo albums. I found old photos at my aunt’s house in Kansas that are just really precious. I think about our great-great-great-granddaughters and grandsons trying to figure out who we were. Here’s our book with so many Potawatomi names, dates, information, plus the portraits,” Hoogstraten said.

Now in her late 60s, she sees Dancing for Our Tribe as the capstone of her long and varied photography and design career.

“It is my legacy,” Hoogstraten said. “With the exception of my family, there is nothing I have done in my lifetime that is more important than this book. Nothing. My interests in photography are dwindling. That door is starting to close for me. But this book is what I did with my life. It’s the most important thing I’ve ever worked on. I can’t imagine anything that could top it.”

Order Dancing for Our Tribe online at cpn.news/DFOT.