Osage Nation celebrates reacquisition of sacred site near St. Louis Arch

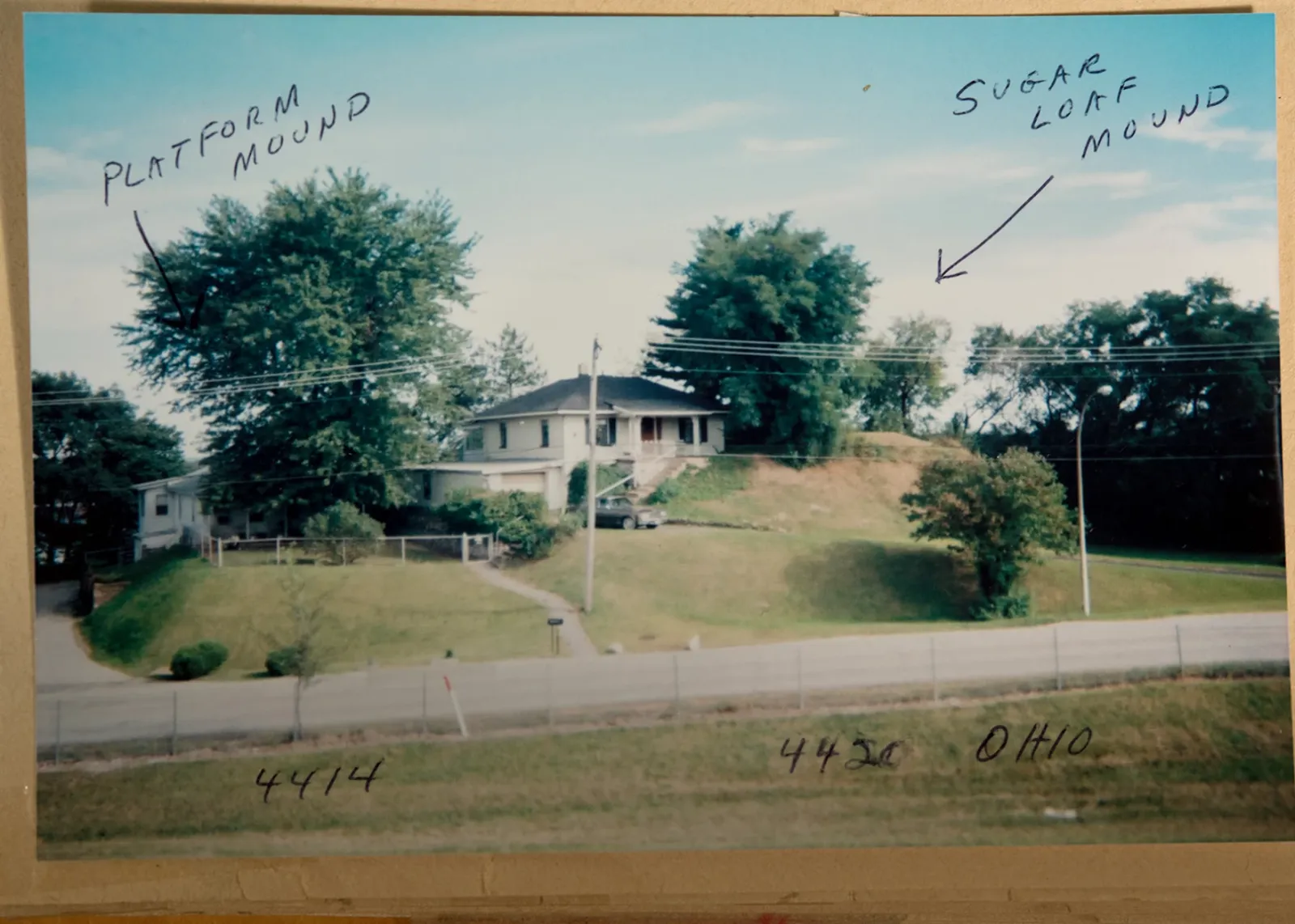

Osage Nation reacquired a sacred site near the St. Louis Arch in Missouri. The site, known as “Suglarloaf Mound,” is now fully under Osage control and is the oldest known human-made structure in the city.

The Osage Nation took a big step in its preservation efforts to restore a sacred site in St. Louis, about a ten-minute drive from the Gateway Arch. The tribal nation said it now owns the entire Sugarloaf Mound, built more than 800 years ago when hundreds of mounds were in the area called “Mound City.”

Despite the significant progress toward safeguarding the Osage Nation’s ancestral homelands, the tribe’s historic preservation director, Andrea Hunter, said those efforts are far from over.

"We have a significant amount of work ahead of us to remove all the structures from the properties and stabilize the mound," Hunter said in a statement. "Now more than ever, our office is dedicated to preserving this sacred site while also educating people about our rich history in the St. Louis area."

The tribal nation has plans to build an interpretative center and is actively seeking funding to further preservation plans.

Archeologists identified Sugarloaf Mound as a Woodland Period burial mound or a Mississippian platform mound, noting it was built between the years of 600 and 1200 AD.

“When the French began construction of what would become St. Louis in 1764, the future city contained possibly hundreds of mounds,” a report co-authored by Hunter said. “While many were relatively small burial mounds situated on the bluffs overlooking navigable waterways, there was also a major Mississippian civic-ceremonial complex located just north of the Gateway Arch.”

Now, many centuries later, after the area was leveled for residences, beer gardens and other uses, the Sugarloaf Mound is the only standing mound in the area. It’s about a twenty-minute drive from the Cahokia Mounds, which is the largest pre-Columbian site north of Mexico and is located on the other side of the Mississippi River.

“The tremendous amount of the Osage Tribe's history that has been lost due to the demolition of ancestral homes, villages, and, most significantly, the mounds in the St. Louis area other than Sugarloaf is devastating,” the report said. “Hundreds of years were erased from the landscape. Moreover, from an Osage perspective, the mounds are sacred. …The Osage, therefore, consider it an honor to protect the last mound of their ancestors in St. Louis for all of the tribes that are heirs of the Mississippian culture.”

Hunter said it was a 17-year journey to get the Sugarloaf Mound under Osage Nation control. Under the leadership of then-Osage Nation Principal Chief Jim Gray, the tribe purchased about one-third of the site for $235,000 in 2009.

She also credits the arts and culture non-profit, CounterPublic, for their support in the reacquisition, including their help with negotiations and the sale and transfer of the land.

Governor Anoatubby leads Chickasaw Community Bank, Ada, ribbon cutting

ADA, Okla.— Chickasaw Nation Governor Bill Anoatubby led ribbon cutting and sign unveiling ceremonies, Friday, Sept. 19, to dedicate an Ada branch of Chickasaw Community Bank, 1100 Lonnie Abbott Blvd., a milestone that signifies a continued investment in the success and quality of life of the people who live and work in the Ada community.

Governor Anoatubby said the bank’s mission, “building better lives for everyone,” reflects the Chickasaw Nation’s commitment to the progress and prosperity of communities.

“By focusing on people and community, and by remaining rooted in the same fundamental principles that have kept Chickasaws united and thriving for centuries, Chickasaw Community Bank has grown to be a leading financial institution, and we are excited to extend that here as we begin this new chapter in the history of Chickasaw Community Bank,” Governor Anoatubby said.

Established in 2002 in Oklahoma City, Chickasaw Community Bank has served the financial needs of Oklahomans and First Americans across the country for the past two decades.

In 2025, Chickasaw Community Bank acquired Oklahoma Heritage Bank, a well-established community bank serving the Ada, Stratford, Roff and Byng communities with a rich legacy of locally focused service.

“For the Chickasaw Nation, this bank is much more than a business. It is a homegrown institution that draws on traditional Chickasaw values and our long history of being a good neighbor and a willing partner in the progress and prosperity of our shared communities,” Governor Anoatubby said. “Since its beginning, the bank has been a resource for economic and community development, primarily in the Oklahoma City area. Now, we are excited to begin delivering those services and benefits here.”

Expanding the bank to Ada, home of the Chickasaw Nation’s headquarters, medical center and several facilities and businesses, represents an ongoing investment in the local community, Governor Anoatubby said, and contributes to the local economy and quality of life of those people who live and work in the Ada community.

The Chickasaw Nation has continually invested in Ada’s growth and progress to strengthen the city in a range of ways, including infrastructure improvements, enhanced public safety and educational opportunities, as well as partnerships with local businesses, local governments and various organizations.

“Today, we continue to serve our people and as a part of that we are committed as ever to serving this community and those surrounding us,” he said.

The new branch of Chickasaw Community Bank, located in the heart of Chickasaw Country, provides a local perspective of the financial needs of area residents.

“That insight, and the relationships we already enjoy, provide tremendous upside and opportunities to offer the best possible financial service while supporting our tribe’s mission to enhance the overall quality of life of the Chickasaw people and our goals of building a strong and sustainable economic foundation that supports our sovereignty, self-determination and ability to provide vital programs and services.”

A History of Service

During the past two decades, Chickasaw Community Bank has helped countless people buy homes, save for their children’s future, build businesses and provide families with the financial means to achieve their dreams. In addition to offering full banking and loan services, Chickasaw Community Bank offers several services designed to serve Chickasaw and First Americans.

“As a tribally owned bank, we possess unique insights into the workings of federal loan programs, which enables us to develop customized approaches to services. We make it a priority to offer financial services to tribes, tribal housing authorities and other tribal entities to help them meet the specific needs of their citizens,” Governor Anoatubby said.

Chickasaw Community Bank was established to bring to fruition Governor Anoatubby’s vision of a tribally owned bank to uniquely meet the needs of Indian Country and the greater community, and to build better lives for everyone. The full-service bank, headquartered in Oklahoma City, is the nationwide leading provider of HUD 184 First American home loans in the nation.

For more information, visit CCB.Bank or call (405) 946-2265.

Scholars, tribal leaders discuss blood quantum

Citizens from multiple tribes gathered to shed light on the controversial topic, its issues, and potential replacements

by Thomas Jackson, Mvskoke Media

TULSA – People from across Tulsa attended a recent discussion at the University of Tulsa on one of the most controversial topics in Indian Country: blood quantum. The Sept. 11 event at 101 Archer, titled “Beyond Blood Quantum: Sovereignty and Tribal Enrollment,” featured a talk with author Norbert Hill Jr. (Oneida); Jennifer Hill-Kelley (Oneida, Kiowa, Comanche), former judge for the Oneida Nation’s Court of Appeals; and Jim Gray (Osage), former Chief of the Osage Nation. Wilson Pipestem moderated the free, public conversation.

Hill, the author of the edited volume “Beyond Blood Quantum: Refusal to Disappear,” spoke of how the issue of blood quantum is, in his opinion, the most important issue that Indigenous people will face in the 21st Century.

“I published two anthologies about blood quantum. It’s a complicated issue. I’ve been in education for a long time, so the books were about community education to try and get people to understand the complexity of this issue.” Hill said.

Hill also made a point of mentioning why holding discussions like this are important. “At the end of the day, we’re trying to figure out how to let people make informed decisions so we don’t terminate ourselves. Our mortality rates are higher than our birth rates, our populations are diminishing, and so we have to figure out how to reinvent ourselves,” Hill stated.

“There’s a sense of urgency there. I believe this is the most important issue Native people are going to face this century, but if we don’t figure this out and find a place for our young people, you know, we won’t survive.”

Another unique presentation was given by Hill-Kelley, who presented evidence via a slideshow of the potential damage blood quantum requirements can do by using the Oneida as an example. The Oneida have a blood quantum requirement of at least one-fourth. This was evidence provided to them by a demographer and analyst.

She pointed out that as time has passed, the number of full-bloods has decreased and the one-half and one-quarter members are increasing. However, due to the blood-quantum requirements, the number of tribal members has stagnated, with most of today’s tribal members being at most one-half or one-quarter.

The Oneida tribe, according to Hill-Kelley, is in danger of “evolving ourselves out” due to the strict blood quantum requirements, as no members below one-fourth can enroll.

Lance Kelley (Mvskoke), one of the organizers, took time to speak about the importance of events like this while also acknowledging that tribes in Oklahoma do have some differences from the Oneida Nation and other tribes in Wisconsin.

“I know it’s a little different perspective here in Oklahoma. In Wisconsin, there’s 11 tribes, while here, there’s 39. It brings another layer of discussion of issues that tribes here in Oklahoma are facing,’ Kelley said.

“The Muscogee Nation is at roughly 100,000 members compared to 17,000 with the Oneida, and the Oneida are one of the largest tribes in their area. And with other issues such as the Freedmen, the number of citizens for the Muscogee Nation is likely to double, so this issue needs to be discussed among many others.”

Peacemaking Court brings traditional principles into Chickasaw Nation District Court

The Chickasaw Nation Peacemaking Court brings Chickasaw traditions, values and customs into modern courtrooms. Resolving disputes for more than 20 years, the Peacemaking Court is a division within the Chickasaw Nation District Court. Peacemaking Court is typically a less expensive, and more timely and culturally sensitive alternative to formal Chickasaw Nation District Court hearings.

“The Peacemaking Court and its circle gives our people the opportunity to reconcile their difference in a safe environment,” Tewanna Edwards, a peacemaker for the court, said. “It’s a place where people have a chance to speak openly and tell their stories and perspectives. In respectful manner, our people have their own say, without an attorney present. Confidentiality at these special gatherings is important.”

Peacemaking Court is a forum for cases to be heard and decided upon using traditional Chickasaw methods. Informal in nature, district judges assign peacemakers to guide and oversee parties in making fair and informed decisions.

As one of more than 30 Peacemaking Courts used by various tribes across the country, the Chickasaw Nation Peacemaking Court puts emphasis on community restoration and repairing relationships. Using Chickasaw values, conflicts are resolved through discussion.

For a case to be heard in the Chickasaw Nation Peacemaking Court, all parties involved must agree to the selection of a peacemaker by the Chickasaw Nation District Court, and they must abide by the resolutions of the Peacemaking Court.

“I consider it an honor to be asked to serve as a peacemaker and to be of service to the district court and the Chickasaw people,” Chickasaw Nation Peacemaker Wayne Edgar said.

According to the late Supreme Court Justice Barbara A. Smith, First American peacemaking courts differ from western mediation.

“Mediation is about an issue, peacemaking is about relationships,” Smith said in a 2014 Center for Court Innovation article. “The key is the peacemakers go in not with the thought of solving the issue. Instead, it’s about helping everyone learn to talk to one another so that they can resolve the problem themselves.”

The core values of Peacemaking Court include respect, humility, compassion, spirituality and honesty. No value carries more significance than another. Participation in the peacemaking process indicates acceptance of these values, both in word and action, and is a commitment between people to move forward from the point of dispute.

“Our people agree to speak one at a time without interruption,” Edwards said. “While holding a talking piece that is passed from one person to the next as they finish speaking, our people agree to speak the truth from their heart and mind — for they came to the peacemaking circle willingly in hopes to resolve their issues. Our people agree to be fair, listen and be respectful of each other at all times.”

Peacemakers are appointed to their position by the Chickasaw Nation Supreme Court. A strict set of guidelines is used during the selection process. As community leaders, peacemakers are respected public servants contributing to positive change. There are currently three peacemakers within the Chickasaw Nation.

Each peacemaker understands Chickasaw culture and traditions, as well as having a core knowledge of modern codes and conduct of the Chickasaw Nation. In instances where peacemakers cannot help to resolve problems, these cases are referred back to the district court to be heard.

“The Chickasaw Nation District Court respects and embraces the Peacemaking Court,” Edwards said. “The court understands we are helping our people heal and find solutions. We are restoring peace and allowing people to move forward while presenting our findings to the judge for review and consideration.”

Once a decision has been made by the Peacemaking Court, a document called the Report of Peacemaking is prepared for the referring district court judge. While the Report of Peacemaking is not enforceable at this point, the district judge can review the report and make Peacemaking Court recommendations enforceable by Chickasaw Nation District Court.

“Peacemaking has been a part of our culture and heritage from the beginning of time and was implemented by our forefathers,” Edwards said. “The Chickasaw Nation officially made the Peacemaking Court part of our law.”