“Welcome to the first day of the new year,” Yahola says to a stunned class of students at Tulsa University. Yahola is a guest lecturer for the Native American studies class.

“Do you mean today is the first day of the new year, Mr. Yahola?” a student meekly asks.

“Yes.”

“But it is July 12th.”

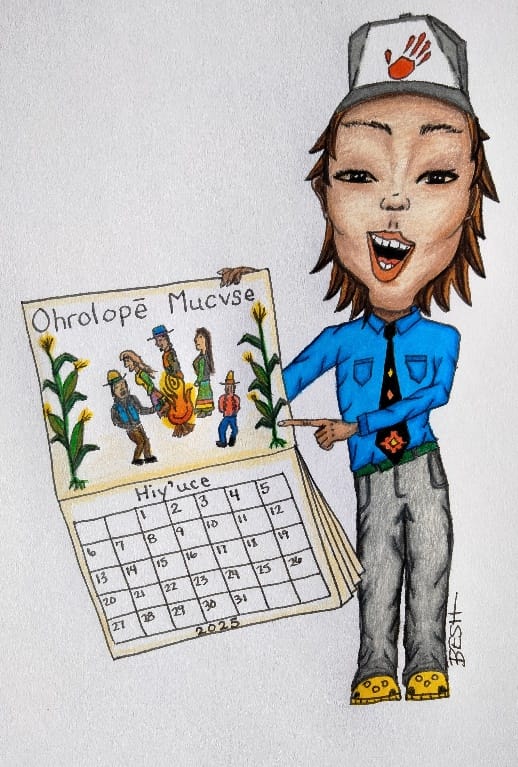

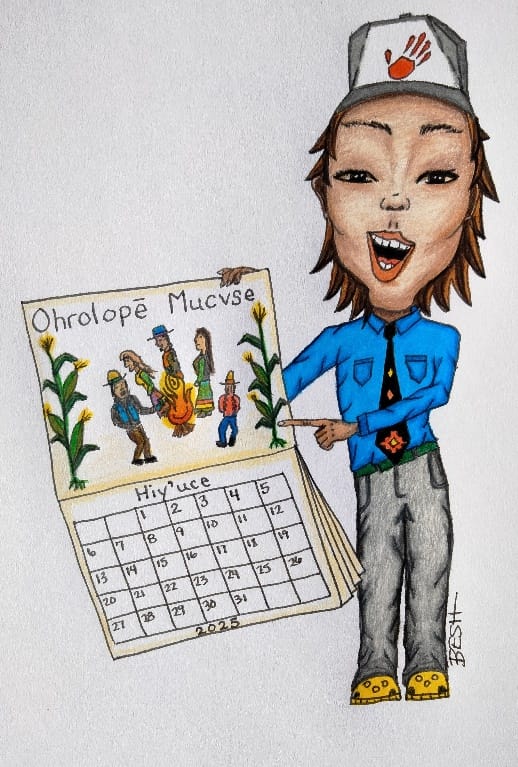

“We Mvskokes, or Creeks if you prefer, would say today is Hiy’uce Palen-Hokkolohkakken,” Yahola replies as he surveys the classroom and holds the rapt attention of the students. “July 12th. But since today coincides with the Green Corn Ceremony at my ceremonial dance ground, it is also New Year’s Day.”

The students lean back in their chairs and exchange quizzical looks. Many sit with nervous smiles. Yahola builds the tension by ignoring the class while unhurriedly shuffling a sheaf of papers. Students begin to slightly fidget. Yahola turns his focus upon the students and slowly gazes from one side of the room to the other. His smile releases the students from the captivity of their anxiety, and they relax their posture.

“Who would like for me to explain?”

“Me!” the undergraduates eagerly respond in unison.

“I realize there is a lot to unpack in my rather cryptic introduction this morning,” Yahola says. “So let us start with today’s date. You know the month as July. For the Mvskoke-Creek people, however, it is called Hiy’uce which translates as little harvest time. It is in reference to the ripening of the first summer crops.”

“You mean like okra, Mr. Yahola? I love me some fried okra,” a student says as the class erupts into gleeful laughter.

“Yes, and lettuce, watermelons, squash, and green beans. These are among the first of the summer crops to be harvested. Thus, Hiy’uce, or Little Harvest Month.”

“So, what is August called, Mr. Yahola?”

“Hiyo-rakko, or Big Harvest Month,” Yahola says. “Those of you who have helped your parents or grandparents tend to a vegetable garden know that August, or Hiyo-rakko, is the time of the big harvest.”

One of the students, Mark Nuttle, raises his hand. Yahola acknowledges him.

“Mr. Yahola, I am sensing a pattern to the Mvskoke calendar. It appears to me that the Mvskoke calendar manifests an intimate relationship with nature and phenomena that occurs during the same period annually.”

“That is true, Mark.”

“So instead of Little Harvest Month, and Big Harvest Month, we have July and August.”

“And do you know where those names come from, Mark?”

Mark scratches his head and shrugs his shoulders. Another student comes to his rescue.

“July is named for Julius Caesar and August for Augustus Caesar. I guess it takes establishing the Roman Empire to get a month named after you.”

“Or be a Caesar who gets assassinated,” another student jokes.

“So, the Western calendar is entirely alienated from natural occurrences. I mean we have the likes of September, October, November, and December. These monthly names are based upon Roman numerals. They are entirely devoid of meaning and any connection to nature.”

“Yes, and they are entirely out of order,” Yahola says. “December, from the Roman decem, or tenth, isn’t the tenth month but the twelfth!”

“No wonder I’ve been celebrating Christmas in October,” another student jokes. “But wait, since October is derived from the LatinOcto, meaning eight, shouldn’t October be the 8th month, not the 10th? This is so confusing! I vote that we adopt the Mvskoke-Creek calendar. It makes way more sense. What are the names of the other months of the Mvskoke calendar and what do they mean?”

“Well since you just mentioned December, let’s start there,” Yahola replies. “December is Rvfo-rakko, or Big Winter; January is Rvfo-cuse, or Winter’s Younger Brother; February is Hotvle-hvse, or Wind Month; March is Tashacuce, or Little Spring Month; April is Tashace-rakko, or Big Spring Month; May is Kvhvse, or mulberry month; June is Kvco-hvse or blackberry month; September is Otowoskuce or Little Chesnut month, October is Otowoskv-rakko, or big chestnut month, and November is Ehole or frost month.”

“I love how the Mvskoke calendar has months named for naturally recurring events throughout the year. It is pleasingly cyclical or circular. It makes me feel more connected to the earth and nature. So different from the antiseptic Western calendar,” Mark says.

All the students nod in agreement. One student in the back of the room stands and raises his hand. He is tall and slender, brown skinned with long straight black hair that falls to mid chest. With his rimless eyeglasses he manifests a studious look. By his look, and his surname, Yahola recognizes him as Mvskoke-Creek.

“Yes, Mr. Tarpalechee,” Yahola says. “Do you wish to comment?”

“I do, Mvhayv (“teacher”),” Tarpalechee replies. “I have an observation to share.”

“Mecares (“do it”),” Yahola says.

“Well, like you, I am Mvskoke. I am very familiar with the Mvskoke calendar. My grandparents taught me. But in my University studies I have learned quite a bit about the Western calendar.”

“Heremahe (“very good”),” Yahola says. “This sounds interesting. Please continue.”

“Well, I think this discussion invites an examination of the origin of the word calendar.”

“Again, please continue,” Yahola says with a knowing smile.

“The word ‘calendar’ derives from the Latin word calendarium meaning ‘interest register’ or ‘account book’,” Tarpalechee says.

“Interest register,” Mark says. “Sounds like something you’d get in the mail from a credit card company.”

“Close. It could be said that the western calendar was created so that lenders could compute interest payments,” Tarpalechee says.

An audible gasp rolls across the classroom. The students sit in disbelief. Mark is the first to break the silence.

“So, the calendar, arguably the foundation of western society, was created so lenders could compute interest?”

“Well,” Yahola responds, “The term calendar is derived from the word calends, the word for the first day of the month in the Roman calendar. Calends, in turn, is related to the verb calare meaning ‘to call out.’ This refers to the announcement of the arrival of the new moon. The arrival of the new moon, the first day of the month, was when lenders collected their debts. Having a calendar was necessary for lenders to be able to compute interest due.”

“It is still so hard to believe,” Mark says, “That the calendar, one of the pillars of western society, was created so that lenders could calculate interest and establish due dates for loan payments. Where did we go wrong?”

Another student chimes in.

“I don’t know about you all but I’m adopting the Creek calendar. That way the bank won’t be able to bill me for my student loans!”

The classroom erupts in riotous laughter as the students nod their heads in agreement.

“I like your plan,” Yahola says. “But you’ll probably have to be a citizen of the Creek Nation for your scheme to have a chance at success.”

“Ah, man!” the disappointed student says.

“To be fair there is a vestige or remnant of the concept of circular time that somehow survives in the western calendar. That is the month of May. So named in honor of the Greek goddess Maia, the guardian of nature and growing plants. Have any of you heard of this Greek goddess?” Yahola asks.

“It’s all Creek to me,” Tarpalechee jokes. The students chortle at his pun.

“The Mvskoke Creek and the Indigenous approach to systems of time keeping and organizing days are very much Earth centered. These Indigenous calendars are constructed upon a framework of the concept of time being circular. This approach is in stark contrast to Western culture which is organized upon the notion that time is linear. This concept is deeply embedded into western religions.

“God’s creation of the world marks the beginning of time. There is a prophetic end time. I would argue that these radically contrasting orientations to time greatly informs how various societies live upon, and relate to, one another and Mother Earth. I would challenge each of you students to give deep thought to how these contrasting orientations manifest themselves in contemporary America. Please be prepared to share your thoughts at class next week.”

“I look forward to it,” the debt-ridden students say. “And I hope to bring my Mvskoke citizenship card.”

“Class dismissed,” Yahola says with a grin.