Native American graduate forced to remove eagle feather from cap sues Oklahoma school

By Molly Young

A Native American high school graduate who wore an eagle plume on her graduation cap is suing her Oklahoma school district after she says two employees forced her to remove the feather.

Lena’ Black says Broken Arrow Public Schools violated her religious and free speech rights during her May 2022 commencement ceremony. Black is a citizen of the Otoe-Missouria Tribe and a descendant of the Osage Nation. Eagle feathers are sacred within many Native American cultures and traditions.

“My eagle plume has been part of my cultural and spiritual practices since I was 3 years old,” Black said in a written statement. “I wore this plume on graduation day in recognition of my academic achievement and to carry the prayers of my Otoe-Missouria community with me.”

Broken Arrow Public Schools employees tried to physically remove feather, damaging it, lawsuit says

In her lawsuit filed Monday in Tulsa County, Black says she was pulled out of a line of graduates and told she had to remove the eagle feather because it violated the dress code. She explained it was not a decoration but a protected religious item. Other classmates, for instance, were wearing crosses. A teacher had also told Black she could wear the eagle plume.

But two different school employees tried to physically remove the feather from Black’s cap, damaging the plume and prompting Black to have a panic attack, according to the lawsuit.

“This unnecessary, traumatic experience ruined Ms. Black’s graduation experience, a day of celebration for her, her family and her community,” the lawsuit says.

The lawsuit names Broken Arrow Public Schools, as well as employees Lesa Dickson and Karen Holman, as defendants. Tara Thompson, a spokesperson for the district, said the school had not yet been served, and administrators could not comment on the lawsuit as a result.

Tribal regalia at graduation:Oklahoma lawmakers vote to stop school bans

Oklahoma’s top legal and education officials have affirmed in recent years that Native students have the right to wear eagle feathers under existing religious freedom laws. Yet Black and other graduates still report resistance.

Lawsuit follows Oklahoma governor's veto of tribal regalia protections

State lawmakers overwhelmingly approved a bill designed to make it clear that students have the right to wear tribal regalia. But Gov. Kevin Stitt vetoed the measure earlier this month, saying that local districts should be able to set their own dress codes for graduation ceremonies.

Several groups, including the joint council of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee and Seminole nations, have called on the Legislature to overturn the veto. But it is unclear whether that will happen. Lawmakers haven’t indicated which rejected bills they plan to take back up before they adjourn May 26.

Without such a law, Native students have to turn to the courts to uphold their rights, said Wilson Pipestem, one of the attorneys representing Black. He is a citizen of the Otoe-Missouria Tribe.

“Ideally, the state of Oklahoma would change the law to make it clear that wearing tribal regalia at graduation is lawful,” he said.

Black also is being represented by the Native American Rights Fund, a Colorado-based legal nonprofit that works to protect the rights of tribal nations and citizens. Her lawsuit seeks compensatory damages of at least $50,000, as well as punitive damages and attorneys fees.

Legal rights:Oklahoma can place some tribal children in foster care without tribal sign-off, court rules

Molly Young covers Indigenous affairs. Reach her at mollyyoung@gannett.com or 405-347-3534.

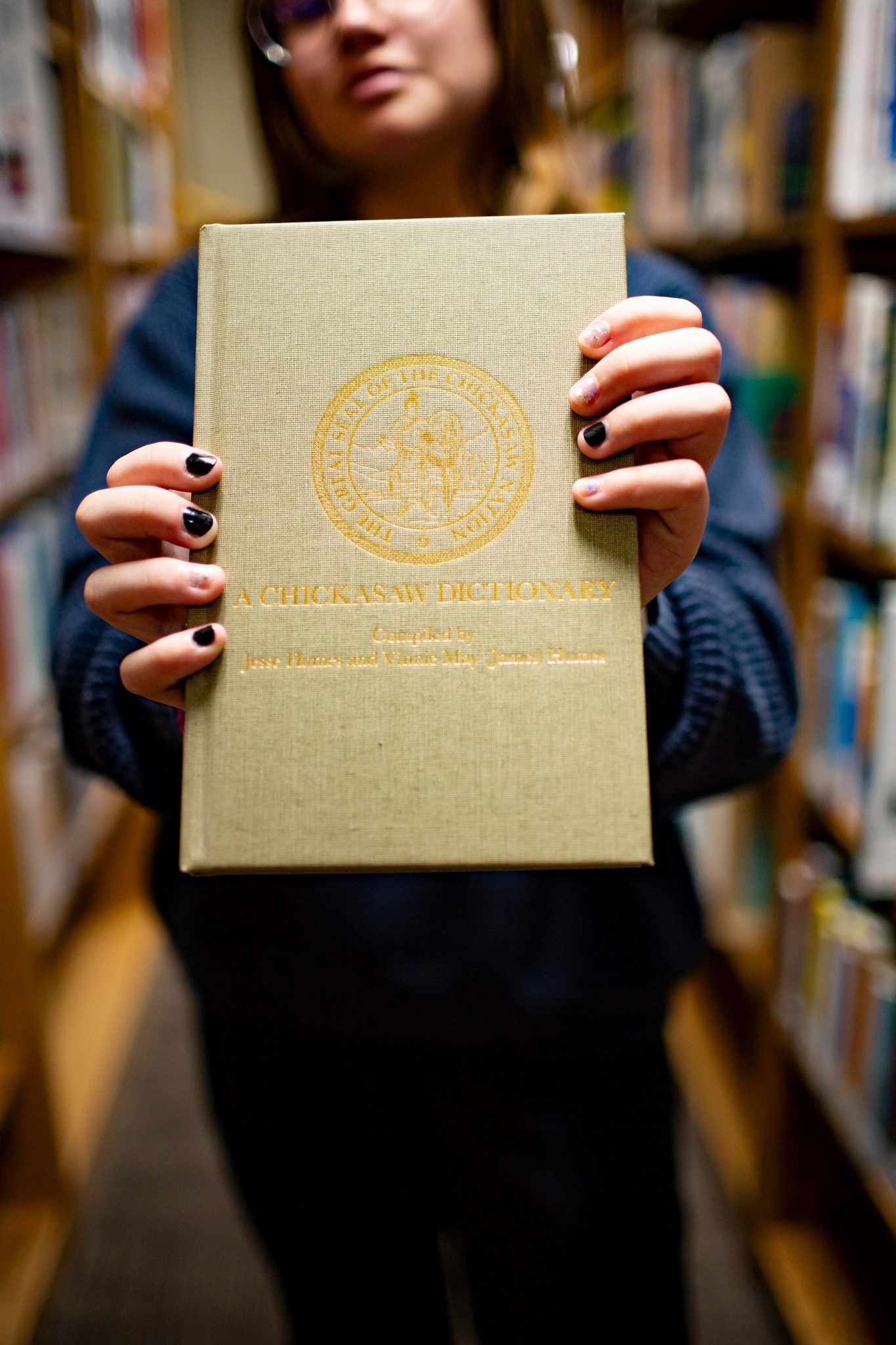

The Chickasaw Nation remains dedicated to language preservation

Preserving the heritage, culture and language of the Chickasaw Nation is of paramount importance.

Two dynamic Chickasaw women and a circuit preacher turned political organizer and activist took steps to ensure the language is available to all through a dictionary and compendium two-volume effort where the language will live in perpetuity.

All are members of the Chickasaw Hall of Fame, the highest honor the tribe can bestow on tribal citizens.

The women – Catherine Willmond and Vinnie May Humes – completed three books which remain the building blocks necessary for introduction to the Chickasaw language and ultimate success at speaking it.

Humes’ husband, Rev. Jess Humes, assisted his wife in completing the first draft of “The Chickasaw Dictionary.” For 2.5 years in the early 1960s, the Humes piled their kitchen table with English dictionaries, pen, paper and later a typewriter, to translate words into Chickasaw.

Their effort was at the behest of Humes’ son, Overton James, who served at the time as Governor of the Chickasaw Nation.

Rev. Humes, a fluent speaker of Chickasaw, Choctaw and English, was very aware of the importance of his cultural heritage and worked to compile “A Chickasaw Dictionary” but died in 1966 just as the first draft was completed.

His wife soldiered on with the task to finish it following his death.

Published in 1973, the book was one of the first efforts to preserve the Chickasaw language in printed form.

Rev. Humes was also highly active in political matters, acting at one time as an advisor to Chickasaw Nation Governor Douglas Johnston. He also represented the tribe for many years in Washington, D.C., and worked to reestablish the governorship as a position elected by the Chickasaw people. He was born in 1887 and inducted into the Chickasaw Hall of Fame posthumously in 1996.

He was a Methodist minister for 34 years, riding on horseback from town to town to tend his flock. He and Vinne Mae Humes were among the driving force behind the Seeley Chapel movement advocating for tribal autonomy.

Vinne Mae Humes was self-educated and did not earn her GED until she was 70. She was born in 1903, inducted into the Chickasaw Hall of Fame in 1991 and died in 1996.

Willmond completed two books. “Chikashshanompaat Holisso Toba'chi, Chickasaw: An Analytical Dictionary” was published in 1994, and “Let's Speak Chickasaw: Chikashshanompa' Kilanompoli',” followed in 2009.

Born March 9, 1922, near McMillan, Oklahoma, Willmond only completed third grade before daily tasks on the family farm ended her formal education. Despite understanding little English for the entirety of her life, her dedication to preserving the Chickasaw language spanned decades.

Ironically, the 1956 federal Indian Relocation Act, designed to assimilate and absorb First American citizens into mainstream American culture – an effort to eliminate First American tribes and their heritage – led to Willmond’s moving to California and introduction to Dr. Pam Munro, a University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) linguist.

Together, they produced the two Chickasaw language books. Willmond worked with Dr. Munro to record more than 40 Chickasaw fluent speakers to complete the dictionary.

Willmond taught linguistics classes at UCLA. She also made guest appearances in First American studies classes at UCLA and addressed audiences at Pomona College and University of New Mexico. Willmond and Dr. Munro completed a book about teaching grammar of the Chickasaw language which was accepted for publication by the University of Oklahoma Press.

Willmond was inducted into the Chickasaw Hall of Fame in 2006. She died Feb. 27, 2022, 10 days shy of her 100th birthday.

Today, many resources are available to Chickasaw citizens to learn, speak and carry on the language that is so vital to Chickasaw heritage.

The Humes and Willmond books are available through Chickasaw Press, Amazon and University of Oklahoma Press.

Additionally, Rosetta Stone Chickasaw is available at no cost to Chickasaw citizens and employees. The learning tool is also available to the general public at a reduced rate. Four Rosetta Stone Chickasaw learning lessons are available, and expansion of the lessons is an on-going goal of the Chickasaw Nation.

The Chickasaw Nation Language Preservation Division is enjoying immense success with other programs aimed at preserving the language.

The Chikasha Academy Adult Immersion Program (CAAIP) is a full-time, 40 hours per week, three-year commitment by students to become conversational speakers. The program is dedicated to creating new Chickasaw language teachers.

CAAIP is an adult Chickasaw language immersion program for novice learners who are paired with master-level fluent Chickasaw speakers and proficient second language speakers of Chickasaw.

Upon completion, participants are expected to be, at minimum, conversational in Chickasaw in the intermediate mid category, as defined by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages' standards.

Additionally, a committee of fluent Chickasaw speakers meets regularly to promote the language and revamp it for use in the 21st century.

For more information, visit Chickasaw.net/Language.

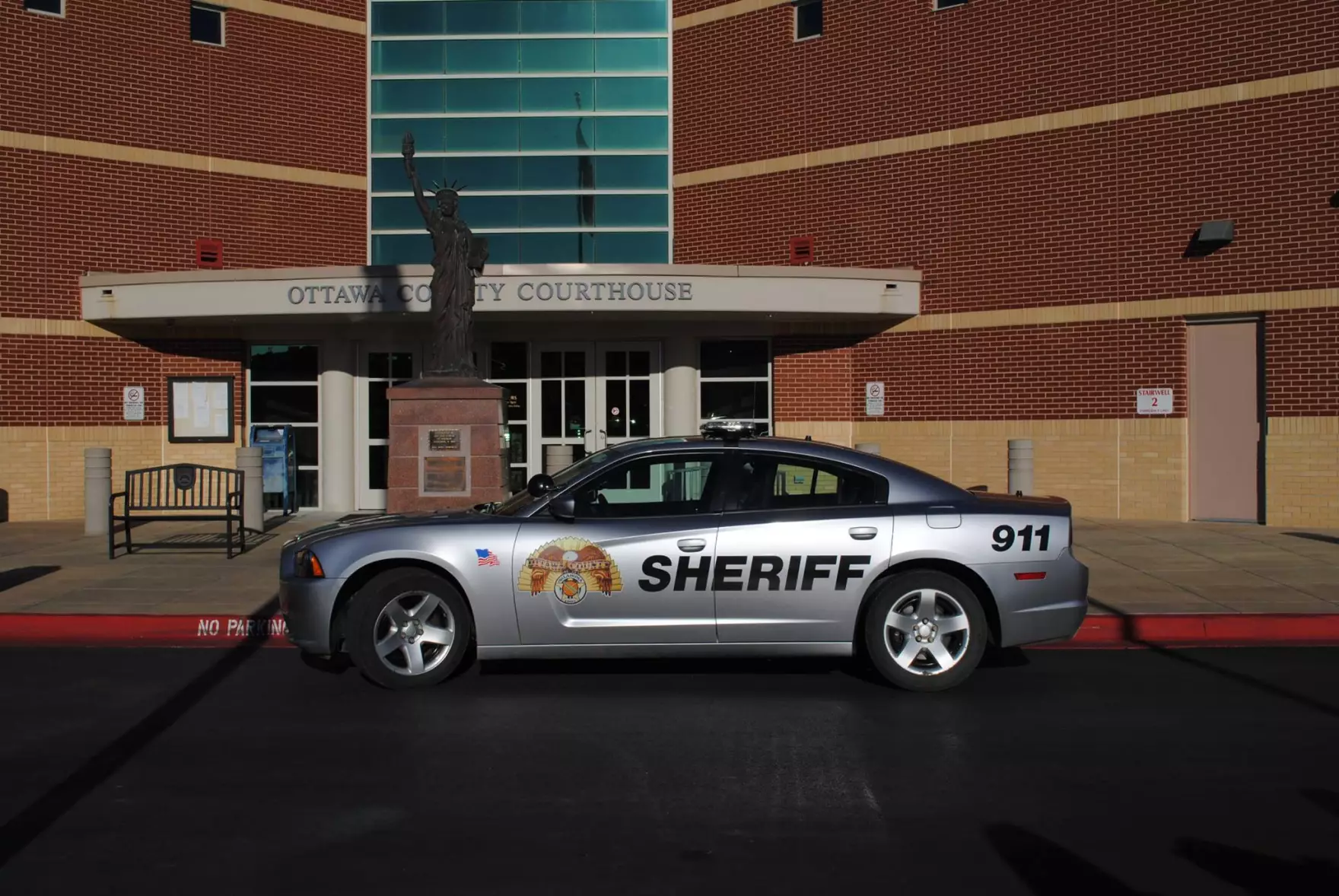

Three tribal nations in Northeast Oklahoma have reservation statuses recognized

Three tribal nations in Northeast Oklahoma have had their reservations deemed as 'never disestablished' by the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals.

Winston Whitecrow Brester, a citizen of the Seneca-Cayuga Nation, filed for post-conviction relief in November 2020 over a string of crimes he was convicted of between 2018 and 2020 in Ottawa County.

After the landmark McGirt v. Oklahoma ruling, Brester claimed he was tried in the wrong court. His crimes were allegedly committed on the Ottawa, Peoria and Miami Tribe's reservations — therefore, he said, he should be tried in federal not state court because their reservations were never disestablished.

Last week, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals sided with Brester after the state objected saying their reservations were terminated and tried to assert concurrent jurisdiction under last summer's Oklahoma v.Castro-Huerta ruling. The state argued that termination era policies in the 1950s by Congress did away with the Ottawa and Peoria reservation, and that Oklahoma should be able to prosecute Brester.

Termination era policies ultimately failed and 20 years later, during the Nixon administration, Congress again committed to its trust responsibility. It passed acts that reinstated the tribal nation's status as sovereigns, including the Peoria and Ottawa tribes. The state argued otherwise, but the court pointed to language within the McGirt decision: "To determine whether a tribe continues to hold a reservation, there is only one place we may look: the Acts of Congress."

That means Congress must expressly say that a reservation status of any tribal nation has been disestablished.

“In sum, the Treaty of 1867 created a reservation for both the Ottawa and Peoria Tribes,” the court said. “These reservations, even if diminished or terminated by each Tribe’s respective termination act, were restored by Congress with the express and unqualified repeal of these termination acts in the 1978 Reinstatement Act as well as with the express reinstatement of all rights and privileges lost in connection with termination.”

The Miami, Ottawa and Peoria tribes all filed amicus briefs supporting Brest's claim.

Last week's decision caps a monthslong dilemma for northeastern tribal nations. In April, Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond sent a letter to Ottawa County District Attorney Doug Pewitt, telling him that the state should exercise criminal jurisdiction while several cases were pending before a decision was reached on the status of those reservations. The letter was in response to cases being dismissed by district court judges or district attorneys because they were waiting on a ruling.

There were three other cases similar to Brester's asking for the Ottawa District Court to dismiss their charges for lack of jurisdiction.

The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals has now ruled that eight tribal nations in Oklahoma have never had their reservations disestablished after the McGirt ruling in the summer of 2020.

Joe Halloran, the attorney working on behalf of the tribes, said he was pleased with how thorough the court looked at termination era policies. He also nodded to AG Drummond for his efforts.

"It's notable that AG asserted control over state's appeal, confirming [the] Court of Appeals up or down question: Does the reservation exist or not?," Halloran told KOSU.

Halloran said it was incorrect for the state to insert the Castro-Huerta argument that the state has criminal jurisdiction

"You don't get to the Castro-Huerta analysis until you rule on the issue of reservation," said Halloran. "We knew our Indian Country existed."

Choctaw Chief Gary Batton Stars in Episode of Netflix’s ‘Spirit Rangers’

Animated series celebrates Native American culture

DURANT, Okla. – Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma Chief Gary Batton appears in the recently launched second season of Netflix‘s “Spirit Rangers.”

The animated show focuses on Kodi, Summer and Eddy, three kids living and working in a national park with their family. But the siblings have a secret: They can transform into spirits and enter the Spirit Park, where they help protect the natural environment, they call home.

Batton voiced a character in the fourth episode, “Chief of the Day.”

“Hollywood is learning something important – audiences love Native stories, especially when they’re told by Native people,” Batton said. “Being asked to represent the Choctaw people and help tell our story and share our culture was an incredible honor – and a lot of fun!”

Series creator Karissa Valencia said Spirit Rangers gives much-needed inspiration to Indigenous kids.

“I just remember that feeling as a little Native kid and just feeling absolutely invisible,” Valencia said. “I love my culture and I’ve just never really seen it represented on screen.”

The show features an all-Native writing staff, including Choctaw Nation member Shelley Dennis.